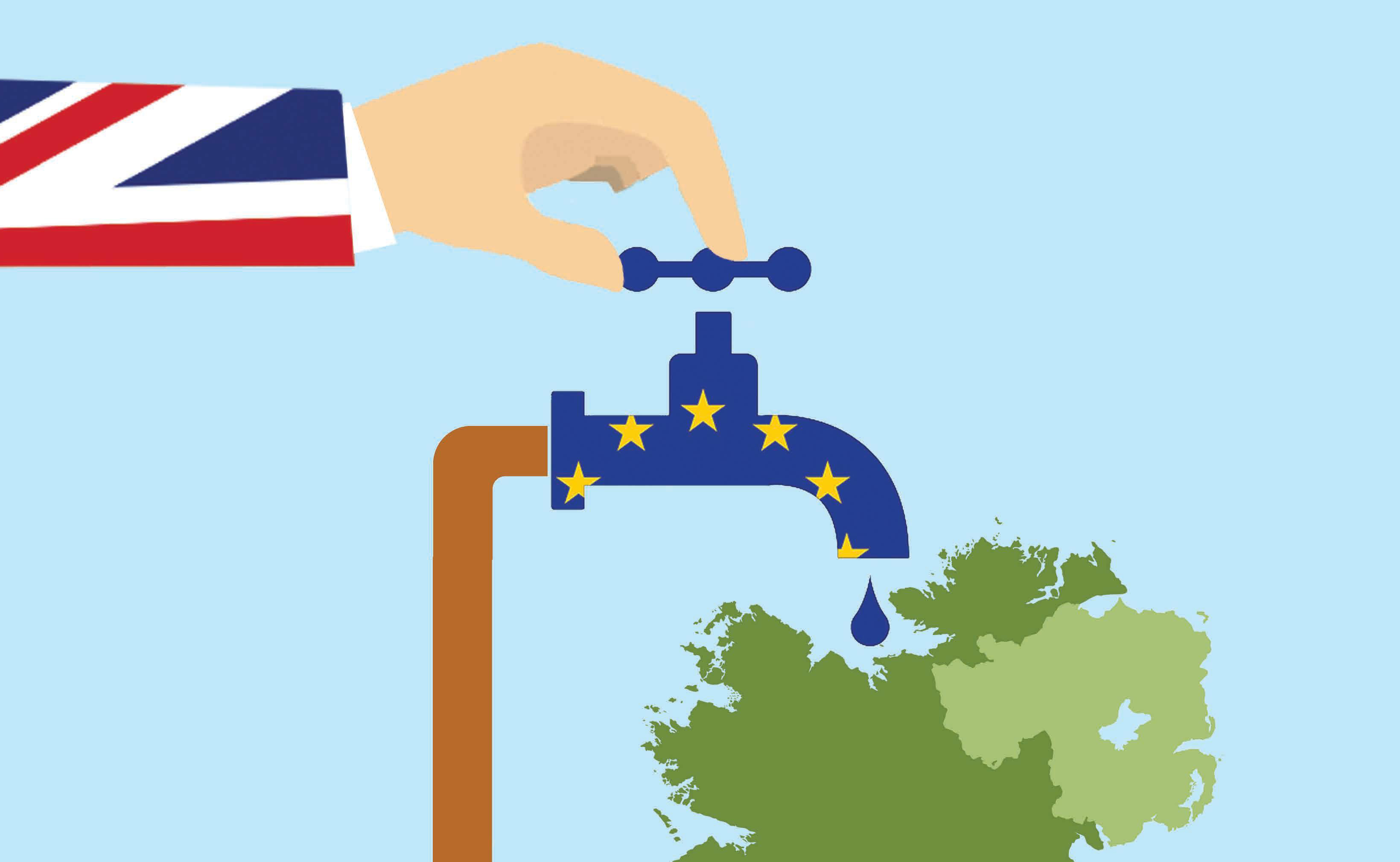

As the shadow of a hard Brexit continues to spread political and economic uncertainty across the UK, a deeper concern is growing in Northern Ireland and the cross-border region where EU funding has been the economic lifeblood for decades.

Following the UK’s decision to leave the European Union last June, a powerful air of unease has engulfed the continent in what has been described as a move into “uncharted waters” and a period of “turmoil and uncertainty” for the UK, Ireland and the rest of the EU. Once Article 50 is triggered, the UK will have two years to negotiate its withdrawal. But no one really knows how the Brexit process will work – Article 50 was only created in late 2009 and to date, it has never been used.

Closer to home, Brexit has unleashed a nebulous political and economic situation; particularly for the border region between Northern Ireland and the Republic. The two economies are deeply interdependent, with significant cross-border trade, integrated labour markets, and many industries that operate on an all-island basis. The border region is particularly vulnerable economically.

Over the past two decades, through PEACE & INTERREG Programmes, the EU has committed approximately €3.39 billion worth of funding to Northern Ireland and the Border Region of Ireland. The future of these programmes and the substantial investment, is looking increasingly precarious.

A recent House of Lords report, Brexit: UK-Irish Relations, warns that of all the nations and regions of the UK, the economic implications of Brexit are greatest for Northern Ireland because of its reliance on EU funding, cross border trade and economic cooperation with the Republic. Elaborating further, the Lords’ report says that EU funding has had a positive transformative effect on Northern Ireland, and on the border regions in particular. Brexit is already giving rise to uncertainty about the availability of future funding, and there is some scepticism over the [British] Government’s assertion that the post-2020 funding gap will be filled. In view of Northern Ireland’s unique circumstances, the report has called on the British Government to explore, during the course of Brexit negotiations, means by which Northern Ireland might continue to be eligible, post-Brexit, to apply to some EU funding programmes, in particular for cross-border projects.

The House of Lords’ aspiration looks increasingly unlikely. As vague as some of the post-Brexit speculation has been, what is becoming clear, as outlined by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire, is that there will be no ‘special status’ for Northern Ireland within the EU post Brexit. Meaning, Northern Ireland, along with all parts of the United Kingdom, will leave the EU on an equal basis.

With that, confusion remains over Mr. Brokenshire’s pledge for the maintenance of a “frictionless” border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Much depends on how committed the British government are to this ideal, whether the EU will push the Irish government to enforce a border crossing with the North or whether Ireland’s government would resist such a plan.

With a soft option for Britain’s EU exit strategy ruled out, fears have been stoked at the likelihood and possible implications of a return to a “hard border” resulting from a ‘hard Brexit’.

Potential implications for Border Region post-Brexit

The one certainty is that Brexit is going to have an impact. The level of that impact depends on the scale of Brexit. And the scale depends upon the outcome from the various negotiations between the European Union and the British and Irish Governments.

While the southern border region should potentially be able to continue to draw upon European Union funds, the future for their northern neighbours looks much more uncertain.

The significance of EU funding to Northern Ireland should not be understated. From 2007-2013 European co-funded programmes in Northern Ireland amounted to an expenditure of €3.45 billion, while co-funded programmes are set to reach an expenditure of €3.53 billion from 2014-2020. A substantial sum by any estimation, and one that increasingly look as though it will evaporate.

There is growing uncertainty surrounding future EU funding of cross-border developments has many people feeling concerned. The border region has benefited greatly – and still relies heavily – on EU funding through the PEACE IV and INTERREG VA Programmes in particular; the future of which are also under threat.

Pamela Arthurs, Chief Executive Officer, East Border Region believes firmly that these EU funds have “helped to transform the border area, but there is still a distinct disadvantage along the border, both North and South.” Adding that any future loss of these funding streams “will be a big loss for Ireland because North and South are involved in both of these programmes and the border region is benefiting”

The big two: PEACE IV & INTERREG VA programmes

The importance of The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and other cross-border EU programmes supported by Horizon 2020, Leader, Erasmus+ and other EU funds notwithstanding, the biggest loss to the border region are the PEACE IV & INTERREG VA programmes.

PEACE IV Programme

The PEACE IV Programme is a unique cross-border initiative financed through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and managed by the Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB). It has been designed to support peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland and the Border Region of Ireland, as well as to promote social and economic stability through actions to instil greater cohesion between communities.

The first PEACE Programme was agreed in 1995 as a result of the developments in the Northern Ireland peace process during 1994. Since then, as the peace process has evolved, the programmes have played an important role in reinforcing the progress towards a more peaceful and stable society.

The PEACE IV Programme key priority areas:

- Shared Education (Total Value: €35.3m / ERDF: €30m

- Aged 14-24 (Total Value: €37.6m / ERDF: €32m)

- Aged 0-24 (Total Value: €17.1m / ERDF: €14.5m)

- Shared Spaces & Services

- Capital Development to create new Shared Spaces (Total Value: €52.9m / ERDF: €45m)

- Local Authority Shared Spaces Projects (Total Value: €28.8m / ERDF: €24.5m)

- Victims & Survivors (Total Value: €17.6m / ERDF: €15m)

- Building Positive Relations

- Local Authority Action Plans (Total Value: €35.3m / ERDF €30m)

- Regional Level Projects (Total Value: €16.4m / ERDF: €13.9m)

INTERREG VA Programme

INTERREG VA Programme is designed to promote greater levels of cross-border co-operation and to alleviate developmental problems exacerbated by the existence of borders. The areas include Northern Ireland (incorporating Belfast), the border counties of Ireland (Monaghan, Leitrim, Cavan, Louth, Sligo and Donegal) and Western Scotland.

Projects must be cross-border in nature and must therefore involve partners from at least two Member States (UK and Ireland). Under exceptional circumstances, up to 20% of the Programme’s allocated budget can be spent outside of the eligible area, as long as tangible benefits to the region can be demonstrated.

The Programme has four key priority areas where it wants to make significant and lasting change:

research and innovation; the environment; sustainable transport and health and social care.

ERDF financing

- Health and social care (€53m)

- Sustainable transport (€40m)

- Improve freshwater quality in cross-border river basins (€20m)

- Improve water quality in transitional waters (€30m)

- Recovery of protected habitats and priority species (€11m)

- Business Investment in Research and Innovation (€15.9m)

- Enhancing Research and Innovation (€45m)

Programme values

Between the two programmes, PEACE and INTERREG have seen nearly €3.5 billion of investment in Northern Ireland and the Border Region of Ireland over the last quarter of a century, with more than half a billion Euro to be invested over the period 2014-2020.

Based on current funding, the combined value of both programmes for the 2014-2020 period is €553 million. The ERDF contribution for both INTERREG VA and PEACE IV is approximately €469 million (85%). In addition, €84 million (15%) must come from match-funding: non-EU sources such as national, regional and local government funding.

The future

According to the European Union, following the outcome of the UK referendum, it can be anticipated that the Northern Ireland PEACE programme will form part of the discussions during negotiations between the UK government and the European Union.

The PEACE programme’s future, in one form or another, appears safe. Speaking on the fate of PEACE funded programmes, Matt Carty MEP said “the European parliament has already passed resolutions that we have put forward calling for the PEACE programmes to continue post-Brexit. It is possible you could see some of that funding coming through. While it’s really important to whoever gets it, it is small enough potatoes in terms of withstanding all the other problems that are going to arise.”

The prospects for INTERREG VA Programme are less rosy according to Mr Carty, who believes this will be the big area of funding lost in the immediate aftermath. “The big area of funding that we’ll see being lost almost immediately is the INTERREG funding and that is really worrying in the short-term. The only way in which that can be resolved is if there is a special INTERREG program that the British government can tie into, but how eager will they be? Probably not so eager, as the only place that has to worry about it is Ireland. The only alternative is to come up with some sort of special designation so that the North stays part of all that.”

Mr Carty added, “If you take European Union funding out of the border areas, north and south, we have a major problem; social, political and economic in terms of the development of the community. It is probably more acute for the North, because the chances of that funding being reinstated by the British government is almost nil. They have been decimating the budget coming to the North for years as it is. They have been really slow to co-finance EU funded projects. You can envisage a scenario whereby the EU together with the Irish government would put in some sort of program to cater for the funding lost by the Southern border region but there is no sense that would happen in the North.”

While not discounting the extremely difficult and challenging time this is for people living and working along the border, Pamela Arthurs believes it is not impossible for future funding to continue, explaining, “there are examples of regions, such as Ukraine, that are not EU members but work with members to draw money down. It’s not impossible but you have to pay [to be included]. So will the British government pay to make it possible to avail of these programmes? It’s just so uncertain. I know people keep saying this but the real issue around Brexit is that no one really knows what’s going to happen.”

Professor Ronaldo Munck, Head of Civic Engagement at Dublin City University, holds a similar view on the quandary that has arisen due to Brexit; “I think in any business, if you don’t have certainty you’ve had it. The fact is we know that business isn’t going to continue as usual. People are just pulling back left, right and centre. In sociology we would call it unforeseen or unintended consequences. You don’t know what is going to come out at the end of it but it’s not going to be good.”

Uncertainty appears to be the biggest theme surrounding Brexit and its fallout. Speaking of future EU cross-border funded schemes, Lord Boswell, Chair of the House of Lords European Union Committee said, “at the moment we don’t know, and I suppose that’s true of the whole Brexit business. But we will start to know when Article 50 is triggered and we get a response from the European Council.”

Adding, the potential loss of EU cross-border funds, “are obviously substantial, though not the only part. Access to markets across the land border, as well and access to people, is part of it and of course that is partly peace process money and structural funds.”

Border Communities Against Brexit 'mock customs post' amid hard border fears.

What can be done?

In the short-term, The Department of Public Expenditure and Reform has worked to secure the programmes. This has been achieved by the introduction of a safeguard clause that would Brexit-proof letters of offer to programme beneficiaries. In the medium-term the objective is to see these programmes successfully implemented out to 2020, through a period during which the UK is likely to leave the EU. The safeguard clause should ensure that this can happen. The long-term objective is to see successor programmes beyond 2020. A regulatory framework for programmes with Third Countries (non-EU countries) already exists at an EU level. PER officials are already working with the SEUPB to examine such programmes and see how they might form a model for North/South programmes post-2020.

However, Professor Ronaldo Munck, believes Brexit is irredeemable bad news for Ireland and its impact is already being felt. “What I know as a researcher working on social inclusion and social exclusion is that, even as we speak, the EU is reluctant to fund anything with a UK partner, which would include Northern Ireland of course. So it is already having an impact. It is not hypothetical. The Welsh Government was going to do something with us on INTERREG and now it’s not.”

Matt Carty, MEP believes the best possible scenario is for the North to be given a special designation, “so that it will remain under EU regulations in terms of produce and trade on an all-Ireland basis. Such a designation would allow it to continue to draw down the European funding that it is currently receiving. The worst case scenario is for the UK to take the North out of the customs union in its entirety, removing it from the single market and removing it from programmes like INTERREG and all the things that go with that. That is a really bad scenario. I suppose then the question is where on that line between the two it actually falls?”

Adding, “we have been saying, at a European level, that under international law people in the North are entitled to Irish citizenship as result of the Good Friday Agreement. That makes them de-facto EU citizens. Even in a post-Brexit scenario they are going to be EU citizens. The EU negotiators have to have a responsibility for the people in the North of Ireland as they are citizens being dragged out against their will.”

Professor Munck is both wary and optimistic to what a post-Brexit Ireland might hold, stating, “as it stands at the moment, it could go either way. There may be a dramatic decrease in North/South cooperation across the board or you could see people beginning to realise the benefits of cross-border cooperation. That depends on Northern Ireland having some form of special status [within the EU]. Which I actually think is possible.”

Amid the uncertainty Lord Boswell believes the difficulties are real, “it is obvious that if you have one part of the island which is part of the European Union and the one part that is leaving, it is difficult to continue with EU funding schemes.”

Adding, that working “cross-border at a technical level is obviously something that has become a habit in practise and it is very desirable to continue. Now if you bring in the issue of EU funding; direct EU, peace process or other EU funding is also in question. We were hinting at the possibility that the UK government would pick up the tab for the missing funds or the EU might be persuaded to continue to help. It’s clearly much more difficult than it was when both parties to agreements were EU member states.”

EU funding in a post 2020 world

For now at least, the already enacted projects running as far as 2020 appear safe, with commitments toward safeguarding the current programmes being made from parties involved.

The European parliament has passed resolutions committing to continue the PEACE programmes in some form or other, post-Brexit and the Irish Government has fully committed to the current programmes and to successor programmes post-2020.

Nevertheless, securing funding for successor programmes post-2020 remains up in the air. Once Article 50 is triggered by the UK government, the negotiations can commence. The Heads of States and Governments of the 27 EU Member States have been clear that no negotiations should take place prior to the triggering of Article 50. Moreover, funding for future programmes will also form part of the negotiation of the next EU Multiannual Financial Framework, to set the annual budgets of the European Union for the period 2021-2028. Proposals are expected from The European Commission for the next MFF by 1 January 2018.

In conclusion, the only certainty that can be drawn is that Brexit will have a profound impact on the Border Region – socially, politically and financially – and it is one that looks increasingly negative.

The evidence suggests the loss of EU funding will have a devastating financial effect. The scale of this impact will depend heavily upon the outcome of the ongoing negotiations between the EU and British and Irish Governments.

What will the future hold for Northern Ireland and the Border Region? As of yet, it remains anyone’s guess. The only certainty is that it will be dramatically different.