The Society of Chartered Surveyors in Ireland (SCSI) recently published an extensive report and recommendations on halting the decline of Ireland’s small towns and rejuvenating their communities. The aim of the SCSI’s report – REJUVENATING Ireland’s small town centres – A Call to Action was to begin a dialogue and encourage the rejuvenation of the heart of our rural communities.

The focus of the report is on small Irish towns outside the catchment area of the five main cities. Recommendations in this report relate to smaller towns, with populations below 10,000. Ensuring the vitality and long-term functioning of these smaller towns is critically important to ensure vibrant rural communities and – making better places to live, work in and visit.

“The decline of our small towns,” says SCSI President Des O’Broin, “in particular their main thoroughfares, is a real challenge and concern for all, particularly those that live and rely on its success for their livelihood.” The SCSI report, he states, is for those community groups and local authorities to adopt so that “practical issues faced by retailers and other business groups can be addressed and therefore help promote a return to a vibrant environment.”

“The importance of town living and having an injection of residential occupancy on our main streets is a recommendation of the report,” he says, “which is encouraging to see.”

Based on interviews and feedback from chartered surveyors working in construction, land and property, the report is a solid attempt at collaboration to solve a problem that ordinarily would be more challenging in isolated groups.

“Every town in Ireland has its strengths and should be given the opportunity to develop a framework in which the community spearheads the rejuvenation of their main street. We envisage the main street offering a place in which to work, live and share the public space whilst understanding the way business is conducted in rural towns has changed,” says O’Broin.

As more streets and towns began to suffer a slow decline, policies and funding schemes have been formulated to counter this. However, it is perhaps only in the last decade, with the onset of the economic crash and the extent of damage it caused, that there has been a clear and determined effort on the part of successive governments to address the fundamental issues that are leading to this decline. Regional high streets have been significantly affected by the recent economic downturn. The impact has been felt throughout Ireland with increasing vacancy rates and a decline in the vibrancy of many rural communities.

Conversely, there are many positive developments, which can change to act as demonstration projects for other towns. Finding a way to effectively share this can be a challenge.

This report is intended for use by local communities and local authorities who are considering or are in the process of interventions to revive and rejuvenate their high streets. It will:

- provide an overview of the trends currently influencing the regional high street and the impacts those trends on the ground,

- consider a range of barriers in enabling a vibrant regional high street,

- identify critical success factors at play, and succeeding elsewhere, in animating regional high streets, and provide pragmatic policy interventions – recommendations to revitalise the regional high street and bring a stronger sense of place and new lease of life to rural communities.

TRENDS

This document highlights several key trends. These include:

- Growth of online retail sales,

- Increasing broadband availability,

- Changing demographics,

- Changing commercial landscape,

- Changing consumer behaviour,

- Increasing vacancy,

- Reform of governance,

- Lack of critical mass.

BARRIERS

A range of barriers to developing vibrant regional high streets are identified:

- Increasing costs and overheads,

- Lack of Collaboration,

- Reduced funding for local authorities,

- Governance challenges,

- Legacy of out of town shopping centres,

- Unattractive urban realm,

- Dominance of the car,

- Lack of connectivity,

- Failure to Innovate,

- Demographic change.

An awareness of the successful measures and interventions that can overcome these barriers is vital. A range of critical success factors are outlined in the report:

SUCCESS FACTORS

- Strong leadership,

- Plan led change,

- Community support and buy-in,

- High quality broadband provision,

- Public realm enhancement,

- Effective management of parking and public transport,

- Use of incentives and dis-incentives

- Simplification of planning,

- Sense of place enhancement,

- Creating vibrancy,

- Marketing and promotion.

There are seven priority recommendations that the SCSI believe are fundamentally important to ensure that regional high streets can thrive and become vibrant and successful community hubs. These include:

Informed high streets – An Irish Towns Partnership should be established to enable sharing of best practice, innovation and mentoring.

Viable high streets – Further development of out-of-town shopping centres in towns with a population of under 10,000, should be restricted to encourage consolidation, and to enhance economic viability and vitality (see theme 1: consolidation and focus).

Collaborative high streets – Inclusive and collaborative engagement mechanisms must be created that includes the local authority, community and business.

Attractive high streets – Public realm strategies must be commissioned for each town and included in town plans.

Living high streets – Local authorities must proactively address vacant buildings in towns to revitalise town centres.

Working high streets – Local authorities and other stakeholders must recognise the changing commercial landscape and attract new high street business through incentives.

Connected high streets – Delivering quality broadband connections to rural areas is fundamentally important for high streets and must be prioritised by government.

There are 13 recommendation themes overall. Each of these themes can be framed in terms of Positioning, People, Planning, Product & Place, and Promotion. SCSI consider these to be the key initiatives required to rejuvenate the regional high street.

Priority Recommendations: Seven priority recommendations have been identified that have the most significant potential for influencing change and animating our high streets.

POSITIONING

THEME 1 Consolidation and Focus: Further development of out-of-town shopping centres in towns with a population of under 10,000, must be restricted to encourage consolidation, and to enhance economic viability and vitality. The National Planning Framework encourages consolidation of urban centres and reduction of urban sprawl.

THEME 2 Coordination and mentoring: An Irish Towns Partnership must be established to enable sharing of best practice, innovation and mentoring. There is a need for a holistic national approach to town and high street development. Consideration should be given at national level to establishing an Irish Towns Partnership, similar to the Scotland’s Towns Partnership model

(www.scotlandstowns. org).

THEME 3 Effective funding: Local authorities should target a range of current national funding mechanisms to facilitate the rejuvenation high streets.

Funding schemes are valuable tools to stimulate and enable investment in high streets. Programmes such as the Rural Regeneration Development Fund should be targeted by local authorities to prove investment in measures such as the urban realm.

PEOPLE

THEME 4 Leadership and responsibility: Dynamic leaders must be appointed to drive positive change on high streets. This should ideally be a town manager role and/or a town architect with a strong understanding of design and urban realm.

Local authorities are the most appropriate agency to engage with community and private sectors and drive change on high streets and have a responsibility to rejuvenate high streets.

THEME 5 Collaboration and engagement: Inclusive and collaborative engagement mechanisms must be created that includes the local authority, community and business. Collaborative development is the most effective way of reviving our high streets.

Groups can be brought together in a variety of ways including town teams, steering groups and/or Business Improvement Districts (BID’s). It is important to gain collective ownership of the change process and giving responsibility to communities can be an effective way of bringing groups together.

The engagement process must begin with a conversation about what people like and dislike about the high street and what are their ideas for the future.

Uniting a community behind a competition, such as Tidy Towns or a bid for funding can be an effective and catalytic way to rally different groups behind a common purpose

PLANNING

THEME 6 Plan-making and visioning: Image-led town design statements must be commissioned to provide focus and structure for high street related development and for the wider town area. For high streets to flourish changes need to be plan-led.

THEME 7 Information and data analysis: Plans and development decisions must be evidence based and where possible use data to determine issues and to monitor change. Stakeholders should use a range of qualitative and quantitative data to provide an accurate baseline of the high street. The Town Health Check process can be a useful tool for undertaking this. Quantitative data can include footfall, vacancy rates, parking occupancy, rental levels, business mix, community assets, public services, customer origins and purpose of visits, where this is compatible with GDPR requirements. Using customers digital footprints ethically can be a cost-effective way of understanding use of place.

This can include travel movements, parking, mobile phone activity, social media interaction and Wi-Fi usage.

Qualitative data can include the commissioning a customer/ visitor survey, establishing the views of those that are using the high street would provide an additional layer of evidence to inform the plan.

PRODUCT & PLACE

THEME 8 Public realm and streetscape: Public realm strategies must be commissioned for each town and these included in town plans. Public realm and streetscape measures, which can significantly improve the appearance of a high street, making it a more attractive place to visit and encouraging increased dwell time, include:

- signage policy to reduce visual clutter,

- landscape and planting policy,

- lighting strategy to highlight significant buildings and ensure people feel safe,

- consideration of ways to balance street space,

- restrictions on use of roller shutters or roller shutters set back from the shop window,

- placing overhead cables underground,

- introducing a colour palette consultation to enhance street frontage,

- coordinated replacement of street furniture, as well as paving and landscaping,

- opening landlocked brownfield sites on back-lands and creating cut-throughs linking other streets to enhance permeability,

- maximising opportunity of natural and built heritage assets – it is this rich unique heritage, in most Irish high streets, that sets each town apart and should be celebrated,

- sponsorship of new public shrub planting, local shop signage painting and decorating, outdoor seating or paint a street by local businesses, hotels and business groups.

Identifying quick wins will galvanise support, while a focus on long term objectives will achieve significant change. Westport has required new developments to install heritage windows, which over twenty years of implementation, has had a positive impact on streetscape.

THEME 9 Transport and accessibility: Pedestrians must be prioritised in small town centres and high streets to encourage increased footfall and dwell time. Making it easy for customers to visit the high street will increase footfall and contribute to rejuvenation.

However, to increase accessibility the public transport network must be optimised, and interchange areas and bus stops made as attractive and comfortable as possible.

Pedestrians must be prioritised with people friendly junctions, a barrier free and de-cluttered pedestrian network. Pedestrians must be guided to and along the high street with effective wayfinding infrastructure.

Ensuring a safe cycle network will make it more attractive for people to visit the high street by bike, with convenient cycle parking also a priority. Many towns are now rationalising car-parking, with a parking strategy part of an overall plan. Recognising that many businesses are dependent on cars being able to park nearby the recommendation is not to remove cars altogether.

Measures to reduce high street car parking spaces, replacing them with seating areas and trees, moving car-parking to back land or edge of town centre sites, and introducing a charging policy that encourages short stays and deters long stays enhance the attractiveness of a town, encouraging people to stay for longer, and spend more.

THEME 10 Proactive planning: Local authorities must proactively address vacant buildings in towns to revitalise town centres. In addition, it is recommended there be national-level consideration of exempted development provisions for bringing vacant buildings back into use in town centres, for example using similar powers to the Derelict Sites Act or section 57 of the Planning Act 2000, as amended.

Vacant buildings impact on the vitality and image of Irish towns, discouraging future investment. It is imperative that local authorities work with owners and overcome issues of fragmented ownership to find new uses using a targeted and coordinated approach. It is important that all stakeholders accept that town centres need to be repopulated as community hubs with a mix of uses including housing, health and leisure, entertainment and arts to enliven town centres and bring buildings back into use. New measures to simplify the process of conversion of commercial use to residential use must be communicated to building owners and other stakeholders to ensure awareness. Local authorities use of Compulsory Purchase Orders should be considered where this will be of benefit to the wider plan for the high street or town – the wider benefit for the local community should be of consideration. Encouraging anchor tenants such as supermarkets back into the town can provide a focus for high streets, increasing footfall and encouraging further investment.

PROMOTION

THEME 11 Incentivising new business: Local authorities and other stakeholders must recognise the changing commercial landscape and attract new high street business through incentives. High streets must become more multi-functional and focus on the demand for experiential retail. The retail mix need to be varied and interesting. The contemporary high street must be increasingly flexible and offer a full range of activities.

Supporting local artisan food and craft retailers can add interest and drive local employment generation.

These retailers can also act as local champions, promoting the high street to a wider audience. The night-time economy is increasingly important and can bring a new audience and invigorate rural towns. A plan for the town should consider ways in which this can be stimulated on the high street. Innovative incentive measures can be utilised to encourage startups, for example a defined period of rates reductions for certain types of industry, including education and experiential retail. It is recommended this could include a 75% commercial rates rebate in year 1, 50% in year 2, and 25% in year 3.

This should go hand in hand with reductions in energy and telecoms costs. Different local authorities currently offer varying levels of incentives. It is recommended that consideration be given to a national high street incentives policy. This could include fit-out costs, which are currently deterring new business from starting up.

Tax or rates rebates or other commercial incentives could be linked to a start-up business course delivered through Local Enterprise Offices. It is further recommended that local authorities review the level of commercial rates, taking a strategic view to encourage reduced high street vacancy rates through reducing rates where possible.

This should be linked to an incentivisation scheme and include measures to maximise clarity on rates system for new businesses.

THEME 12 Marketing and placemaking:A marketing and promotional strategy must be produced for each town focussing on measures to rejuvenate the high street and attract increased footfall.

The collaborative strategy must focus on what the town offers and what makes it special. This can include identification of a brand, who the audience is, how it will be marketed and who will act to make things happen. Development of a programme of festivals and events can bring a buzz to high streets, and appeal to families and the Millennial markets. Businesses should be engaged in developing such a programme as they can act as a key promotional tool. Local authorities could focus on ensuring a space is available for events and markets, with appropriate lack of clutter and easy access to power for lighting, amplification etc.

The local media can be a powerful tool in promoting the high street and communicating events and festivals to a wider audience.

As part of the strategy, high street stakeholders should be encouraged to unite behind a destination promotion vehicle e.g. co-opetition marketing with a combined marketing budget.

THEME 13 Delivering connectivity: Delivering quality broadband connections to regional areas is fundamentally important for high streets and must be prioritised by government. High speed broadband is an essential service and is necessary to enable the rejuvenation of high streets. There are several reasons for this.

Technology can be used to facilitate new ways of working, for example hot desks and digital hubs, and serviced offices which offer a major opportunity for creating spaces for people to work in local towns, retaining people through the day. In addition, to compete with the online market high street business must have an online presence and require effective broadband to do so.

To encourage increased footfall, dwell time, and online engagement local authorities must provide free wifi as a public service. Innovative approaches from elsewhere should be considered, such as a ‘dating app’ for property owners and startup businesses. For example, an online tool could be developed to enable the listing of available properties through the Local Enterprise Office and to link this to those seeking space.

Changing Commercial Landscape

Aside from online shopping, perhaps the most significant challenge to traditional town centre retailing has been the growth in numbers of out-of-town shopping centres and retail parks. Ireland’s first shopping centre opened in 1966, since then growth has been extensive, with shopping centres equating to 1.98 million square metres as of December 2015 . In total, there are 202 purpose-built shopping centres throughout Ireland, with Dublin alone accounting for 32% of the overall stock. Since 2013 there has been very little development in this area, with development primarily occurring in the form of extensions to existing premises. For example, approximately 27,900 sq.m was completed in the form of extensions in 2015, the majority of which can be attributed to Liffey Valley Shopping Centre in Dublin.

Retail parks also encountered issues during the downturn, and similar to shopping centres there has been very little construction since 2009, with no known developments planned. Total stock of retail parks stood at 1.17 million sq.m as of 2012, with more recent figures unavailable. Of this total, 24% is found in Dublin, with 8% in Limerick, 7% in Cork and 4% in Galway.

The landscape within which retailers and other businesses have dramatically altered in recent years. Globalisation and online retailing have led to an influx of international brands and retailers into previously closed or peripheral markets. This increased competition has proven to be detrimental to many smaller, indigenous brands. Larger retailers expanded their global presence at dramatic rates and this has added to a major restructuring of the high street. Expansion of major retailers and brands into almost every urban settlement of significance, often with multiple representations, is obvious in Ireland.

Alongside this, consumer behaviour has changed drastically, with the concept of ‘’experiential’’ shopping now widely proclaimed as the key driver of town centres. Essentially, consumers now spend less on comparison goods and instead spend more on experiences, such as food, beverages and services such as beauticians and barbers. This trend is reflected in the composition of our high streets now, with town centres switching from locations of predominantly comparison stores to ones where services, cafes, bars and restaurants dominate.

The CSO Business Demography release uses revenue data to provide a summary of enterprise activity and employment in various industries. By analysing data between 2011 and 2016 a picture of broad trends across counties can be drawn. Perhaps the two most pertinent industrial categories for this study are the ‘Accommodation and Food Services’ category, and the ‘Wholesale, retail trade and vehicle repair’ category.

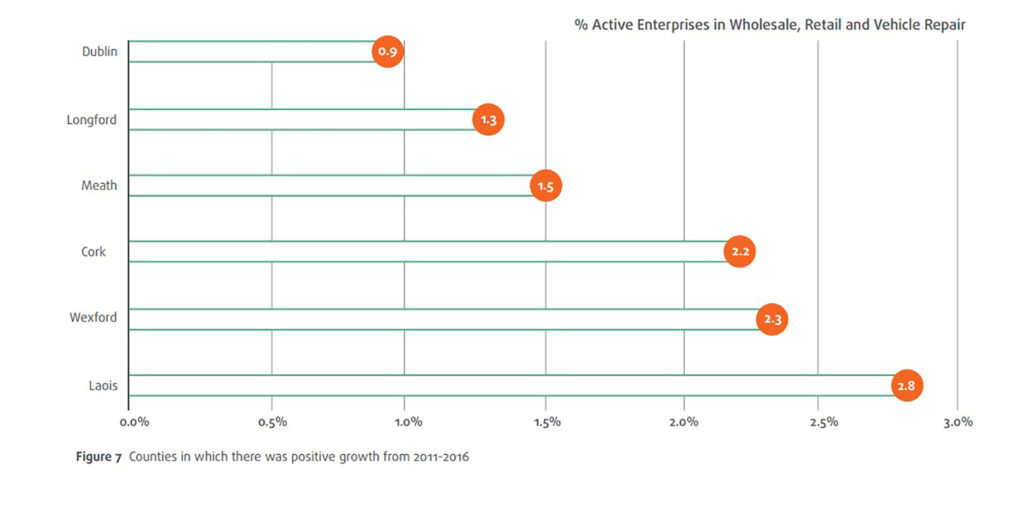

Although both categories contain a range of enterprises, many not traditionally found on high streets or in town centres, they offer a useful insight into trends. Almost every county has seen a decrease in the total number of active ‘Wholesale, retail and vehicle repair’ enterprises between 2011 and 2016. Figure 7 shows the only six counties where there was growth.

It is a clear indication of the difficult environment that exists for retailers that 20 of the 26 counties recorded a decrease in the total number of active enterprises in this category. The ‘Accommodation and Food’ sector has had a more mixed result for enterprises, with fifteen counties recording increases in numbers of active enterprises, while eleven saw decreases. Longford, Meath and Dublin all scored well in this respect, while Roscommon, Laois and Tipperary performed poorly.

In the US there have been increasing numbers of store closures in recent years. Many reasons can explain this; online shopping is growing, consumers are now spending more on experiences than on items (2016 was the first time ever that Americans spent more at restaurants and bars than at grocery stores), and the retail environment is too large so contraction was inevitable.

Larger ‘’bigbox’’ stores, clothing stores, and fashion department stores have shut, however other areas of the sector are expanding like grocery, discount stores and sports goods.

Growth in demand for experiences over products

Increasing vacancy due to the competitive, and dynamic nature of the retail environment in recent years, vacancies have become more commonplace on our high streets. While this is undoubtedly a problem, it also has knock-on effects. Vacant premises that lie unoccupied for a sustained period can create a negative perception of a place. This, in turn, can be off-putting for both consumers and any potential investors or retailers, who will see vacant premises as an indication of poor health, creating a vicious circle of decline. Residential vacancies also contribute to the overall perception of a place and therefore understanding the trends in this area will provide a useful indicator. The CSO produce a dataset which highlights the changes in residential occupancy in 845 settlements across Ireland. This data is available for both the 2011 and 2016 census and the chart overleaf gives an indication of the change that has occurred in 845 settlements between 2011 and 2016. Only 3% or 23 settlements saw no change in the number of vacant residential properties. Almost 1 in four settlements – 23% – have shown an increase in residential vacancy over the 2011-2016 period. A more positive indication is that 74% of the 845 settlements recorded a decrease in residential vacancy.

This indicates that as the housing crisis is intensifying, more vacant homes are coming back into use. Commercial vacancies are not recorded by the CSO, however, Geodirectory release annual reports outlining commercial vacancy rates in a hundred settlements across the country. Geodirectory, an affiliate of An Post and their database, is utilised for the delivery of post throughout Ireland. For this study, Dublin is excluded as it is included multiple times based on postcodes.

This leaves 79 settlements of which 24 recorded a decrease in commercial vacancy rates between Q3 2013 and Q4 2017.

The remaining 55 towns (i.e. 70%) all recorded increases in commercial vacancy rates over the 2011-2016 period While there are undoubtedly some anomalies and extenuating circumstances that may explain a number of these increases, it is still a worrying statistic and highlights difficulties many towns are encountering. The SCSI Commercial Property Review and Outlook Report offer some interesting insights into the current commercial landscape from the perspective of Chartered Surveyors. Office investment continues to perform well in Dublin and Cork, while retail rents have remained steady across the country.

Demand for high quality office space is expected to continue to rise, which is perhaps an indication of the changing composition of the labour force. Regarding retail rents, it is stated that rents remain substantially below Celtic Tiger levels, even though the economy has returned to similar levels. While there have been several attempts by national government to stimulate development of vacant sites, derelict and vacant buildings, this has had limited success.

Both ‘’carrot’’ and ‘’stick’’ measures have been attempted, through tax reliefs, grant offerings and levies, but there remains a significant stock of vacant dwellings, derelict buildings and brownfield sites. There is a common perception that current measures do little to force large property investors and international vulture funds to release this withheld stock.

Therefore, more punitive measures are required. There is a requirement to counteract what is termed ‘’market disincentives’’, which essentially is the way in which growing markets make it cost-effective for a property owner retain underutilised lands. Because the value of the lands will increase as the market grows, the longer an owner waits, the greater their eventual return.

An alternative mechanism is the introduction of a land value tax (LVT) which could replace contentious taxes such as the property tax. This tax is the best mechanism for reducing land hoarding. Every bit of land with productive potential would be liable to pay this tax, however, each site is taxed on a proportion of the current rental value. This means that more rural locations would not suffer from excessive costs, while sought-after locations such as Dublin would see higher rates. It is generally accepted by economists that LVT deters land-hoarding and contributes towards reducing inequalities.

Governance

A restructuring of how society is governed is continually at play, with dominant forms of governance emerging for sustained periods before being replaced by another. Numerous terms have been assigned to the form of governance or political agenda that has been dominant in western democracies for the last half century; neoliberalism, capitalism and entrepreneurialism, to name but a few. This style of governing is market-driven, with governments at all levels taking a less proactive approach to governing, and ceding control of many services to the private sector. These changes to a more entrepreneurial style of governance have seen unprecedented levels of economic growth, however, it has also created conditions where nearby towns are forced to compete for capital, in a zero-sum game. Local government has often been consigned to a minor role, while the national agenda is pursued. Indeed, the ability of local authorities to influence the direction of development and the fortunes of their own towns has been dramatically reduced. In Ireland, various government reforms and policies over the years have contributed to a fractured governance environment. The Local Government Reform Act 2014 made provisions for the dissolution of town councils, the creation of municipal districts and the merging of several separate local authorities. Although these reforms were touted as a way of creating a more efficient and accountable form of governance, there have been claims of a federalisation, where decision-making has become centralised or removed from where it is required. Lack of funding has also led to a loss of essential local authority staff, such as Town/Municipal architects meaning there is no ‘’champion’’ within the Council to steer appropriate development. Local authorities have limited means through which they can raise revenue. Rates, parking fees, development contributions and property taxes are the key sources of income. While local authorities have been, in some cases, designated more powers to influence, they have not received additional funding. This, some key influencers have argued, has forced many to increase the fees in those areas they have control over, such as rates, which in turn disproportionately impacts smaller retailers.

Lack of critical mass Ireland is unusual in Europe in terms of the structure of the urban environment. Traditionally the Irish have been predominantly rural, indeed up until relatively recently a majority lived in rural locations. The island was composed of many small towns and villages, with compact centres and a clear differentiation between urban and rural. The compactness remained for centuries, until in the 1950s and 1960s there was an increase in urban development, with almost two thirds of us now living in urban areas according to the 2016 Census. However, in many cases development was an unstructured sprawl spreading from the core. Urban sprawl is not limited to Ireland. It is a global epidemic which originated in the US with the development of the motorised vehicle. Sprawl has been facilitated by the emergence, at a large scale, of the motor car which allowed a person to travel longer distances than previously possible. Our urban environment was no longer limited by distances and could now develop outwards, in lower densities, because the car allowed it. Short-sighted development, destruction of older buildings, the growth of the car and the enlargement or roads all contributed to the destruction of the traditional rural streetscape. Our market towns now saw their central square become a parking garage. Streets that were never designed with the car in mind, now must accommodate vehicles in huge numbers. Ireland, as a traditionally rural country, has always had dispersed development. Therefore, although not caused by the car, this dispersal has been enhanced. With comparatively very few major urban centres, Ireland is instead dominated by a collection of smaller towns. This is problematic for retailers as they do not have the required critical mass in smaller towns to thrive. Similarly, supply chain issues are caused by the poor regional transport network, which cannot be sustained due to our dispersed population.

There is no reason why rural living and working cannot be attained using all the available planning, technology and funding tools that we have currently. It is possible. It just takes a longer term commitment to a more sustainable society with the right central government backing and empowered local communities and county councils.