Jenny Deakin from the EPA outlines the problems with water quality in Ireland, and describes the development and implementation of Ireland’s 2nd Cycle River Basin Management Plan (2018-2021).

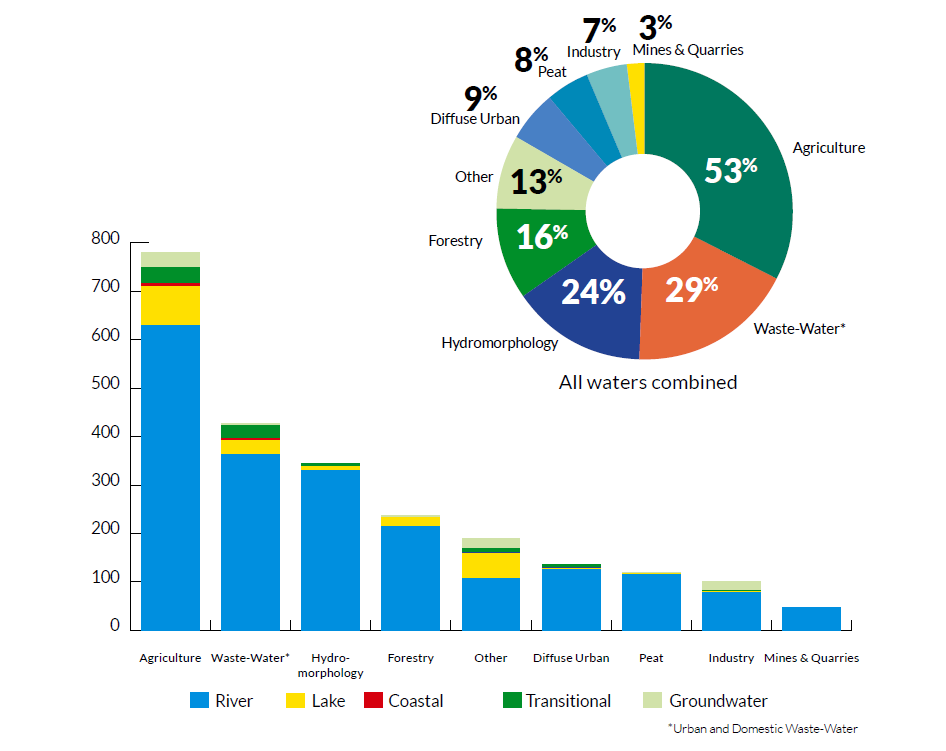

The most common water quality problem in Ireland is caused by the impact of excess nutrients from agriculture, domestic and urban waste water and other activities on rivers and lakes where they damage the ecology. Sediment is also a problem in places, as well as physical change and damage to our waterways. Despite significant efforts to address these problems over many years, water quality has not improved nationally; recent reports from the EPA have found declines in the quality of our rivers and high status waters.

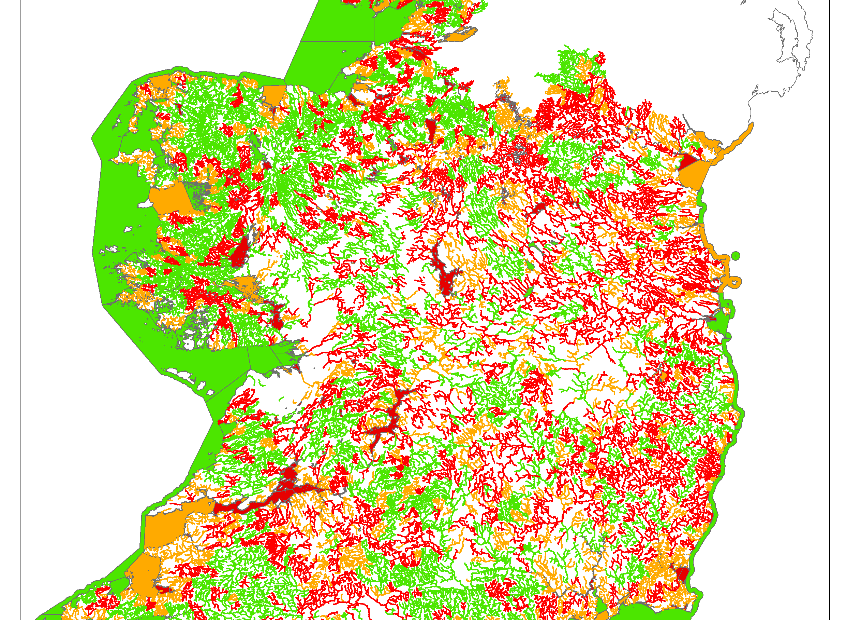

To address ongoing water quality challenges, Ireland’s latest River Basin Management Plan was launched by the Minister for Housing, Planning and Local Government on 17th April 2018. The River Basin Management Plan sets out to protect and restore our waters – rivers, lakes, ground waters, estuaries and coastal waters in line with the Water Framework Directive. The Directive requires all EU member states to achieve at least Good Ecological Status in all their waters by 2027. The Minister has made a plan that covers the whole of the country, replacing 7 plans from the first planning cycle. Critically, the Plan sets out 190 specific priority areas for action where work will be focussed between now and the end of 2021 to improve water quality in Ireland (Figure 1). The identification of these areas was based on a substantial scientific assessment by the EPA in collaboration with local authorities and other public bodies. The areas and the reasons for their selection are available at www.catchments.ie/areas-for-action. New implementation teams are now in place to progress work in these areas.

What we learned from the first cycle plans

Arriving at the actions set out in the latest plan was a substantial task. The first plans proved less effective than expected and did not achieve a nett improvement in water quality, despite significant investment in agri-environmental schemes, on-farm storage and urban waste water treatment. Three key learnings from the first plans that helped to shape a new approach for the second plan were that:

1.The governance and delivery structures in place for the first cycle were not as effective as expected

2. A multiplicity of river basin districts did not prove effective, either in terms of developing the plans efficiently or in terms of implementing those plans

3. Targets and objectives were not founded on a sufficiently developed evidence base.

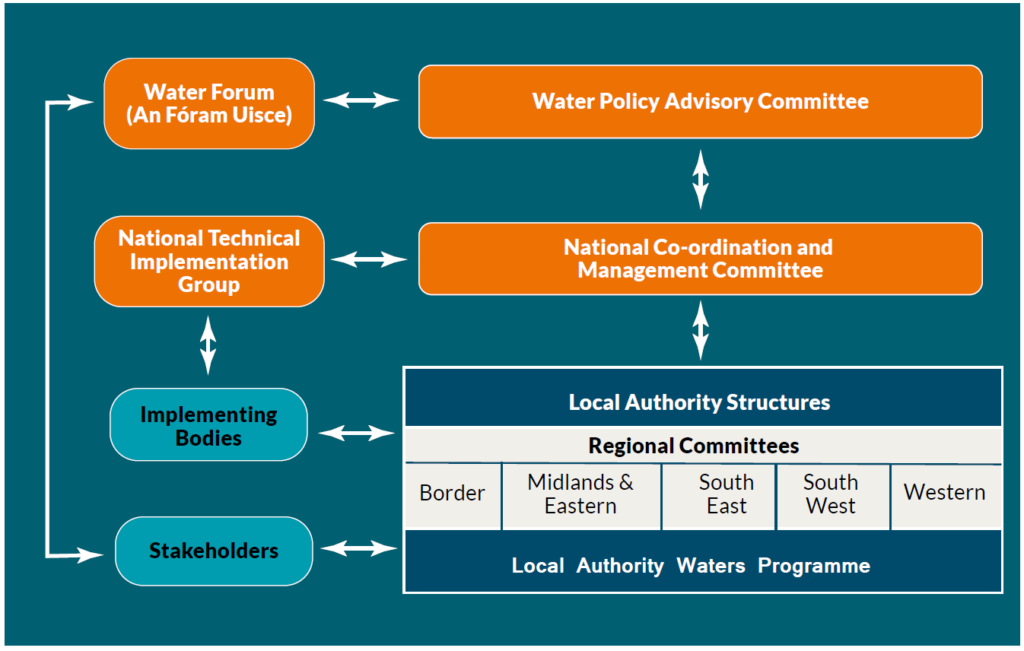

The new plan has defined new effective and efficient national, regional and local governance structures to deliver on the plan. The plan also provides for coordination between these structures to ensure integration of scientific understanding of the problems to be addressed, policy development and on-the-ground delivery. A key change is a move to a more collaborative and evidence-based problem solving approach which seeks to involve local communities in protecting their water resources. There is now much greater clarity about who does what, how things are done, when they are done and at what level. The focus is on working together to achieve improvements in water quality.

The targets set in the latest Plan are based on sound evidence. The plan sets out to continue to ensure effective national measures to address pressures are implemented throughout the entire country. Where such broad-based measures are not sufficient however, the delivery of supporting measures must be prioritised, ensuring the implementation of “the right measures in the right place”.

New teams on the ground to implement the work

Local Authorities are leading the implementation of the actions to deliver water quality improvements in the 190 areas for action. It was recognised in the preparation of the plan that there needed to be an additional emphasis on addressing diffuse rural pollution. This has led to two new inter-connected implementation services being established and resourced (90 new staff in total). The first of these is a Local Authority Shared Service – the Local Authority Waters Programme. It is made up of two teams: one to engage with communities in the protection of water, and a second to undertake assessments and follow up with stakeholders to seek solutions to those problems.

(Further information on the Local Authority Waters Programme is available at http://watersandcommunities.ie/).

The second service is a joint dairy industry-Departmental initiative known as the Agricultural Sustainability Support and Advisory Programme. Thirty farm sustainability advisors are working with farmers in the areas for action to address the local agricultural problems that are identified. All these teams are working together to drive measurable and sustainable improvements in water quality in these 190 Areas for Action between 2018 and 2021.

The EPA has been playing its part by developing the evidence base to underpin the Plan. This is not a simple task as there are many pressures impacting on water, not all of which are significant (i.e. actually contributing to the water quality issues). EPA carried out national assessments to identify which pressures are significant. The work involved almost 50-person years’ worth of work, over 140 datasets and a range of modelling tools. Local information and experience from local authority and Inland Fisheries Ireland staff, and a wide variety of other public bodies, was captured and considered. This led to a rigorous assessment of the risk of individual areas (called water bodies) failing to meet their objective (Figure 3) and identification of the pressures causing the water quality issues in each water body that is “at risk”.

The significant pressures on our water bodies at the time of the assessment can be viewed on

www.catchments.ie/maps. Agriculture was found to be the most prevalent significant pressure impacting on “At Risk” water bodies (53%), which is not surprising given that agriculture is also the most prevalent land use (Figure 4), but there are also a range of other significant pressures.

This evidence base has been key to assisting in the identification of the 190 areas where action is now being focussed. The EPA has also provided the new implementation teams with the tools, science and training needed to support their work. EPA will now be tracking and reporting on the implementation of the plan as the work of the implementation teams and other national level actions is progressed. In the meantime, EPA is starting to build the evidence base to support the next River Basin Management Plan in conjunction with the Local Authorities Waters Programme. Water bodies that are currently ‘Not at Risk’ could still deteriorate in the future, and therefore need ongoing protection, including implementation of best practice management strategies, and prevention of accidents.

Planning for the 3rd cycle

While this implementation is underway; planning for the 3rd cycle plan has started. The Minister recently published the draft timetable and work programme for the River Basin Management Plan 2022 – 2027 for public consultation. The consultation document sets out the main steps and milestones in the three year process to the next River Basin Management Plan, which is due to be published in December 2021, and the steps which the Department will take to ensure comprehensive engagement with the public and all stakeholders. This consultation is open until the end of June 2019.