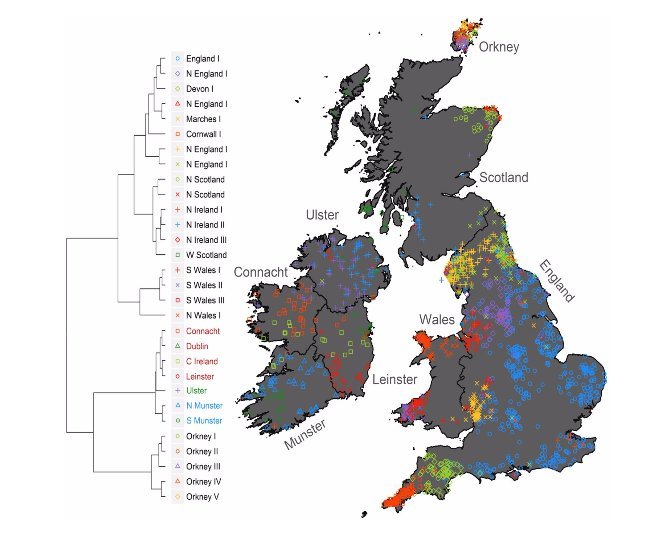

The study analyses the genetics of ten cluster groups aligned with the provinces of the Island.

A team of geneticists from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI), along with genealogists from the Genealogical Society of Ireland have published the first genetic map of the people of Ireland in the journal Scientific Reports.

The Irish DNA Atlas; Revealing Fine-Scale Population Structure and History within Ireland is a live study which has currently compiled DNA samples from 196 Irish individuals with four generations of ancestry. Researchers compared the Irish samples of DNA with thousands of others from across Britain and Europe.

The study reveals patterns of genetic similarity, including subtle differences, between ten distinct cluster groups that align with the provinces of Ireland.

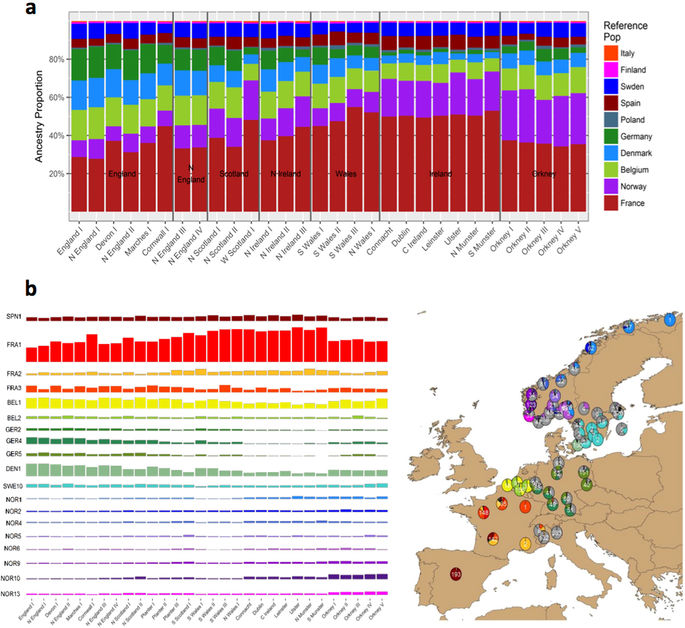

Seven of the clusters were of ‘Gaelic’ Irish ancestry and three of shared British-Irish ancestry. It was also detected that 20% of the Irish genome derives from Norse ancestry, specifically of Viking origin, and the impact of the Ulster Plantations on Irish genetics is analysed.

Prof. Gianpiero Cavalleri of the RCSI directed the research for the Irish DNA Atlas. According to him, the formation of Munster today, with north and south, could have been influenced by historic dynasties, such as the Dalcassians and the Eóganachta.

The Dalcassians, or Dál gCais tribe of Ireland, can be notably associated with the legendary high king Brian Boru and were primarily based in north Munster. The Eóganchta dominated the south of Ireland from the 6th to 10th centuries and originate from Conall Corc who founded the dynasty in the 5th century in Cashel.

Prof. Cavalleri said:

“Everyone who is in the study has all eight of their great-grandparents born within 50km of each other. To get into this study you have to have that tied ancestry. When we look at the DNA of all these people, we see they go into groups of 10. When we then plot each individual back on to the Irish map by where their great-grandparents are born, we can see that people who are born close to each other tend to fall into the same groups and the groups correspond broadly

with the provinces of Ireland.”

Those who fit the criteria of the study are urged to email Séamus O’Reilly from the Genealogical Society of Ireland via irish.dna@ familyhistory.ie to get involved. This research goes further than simply comprehending our ancestry. The Irish DNA Atlas provides a stepping stone for future efforts to understand

and treat genetic diseases.

Findings from this study will contribute to the vision of the new FutureNeuro Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre, which is seeking to improve the diagnosis of rare neurological disorders and personalise treatment.

What is the background to The Irish DNA Atlas?

“It was a project we started in 2011. It was launched at the Back To Our Past Conference and it was launched in partnership with the Genealogical Society of Ireland so it was a collaboration between ourselves at face value as geneticists and the Genealogical Society of Ireland genealogists.

“It was funded by Science Foundation Ireland in 2014 and we’ve been steadily collecting samples since 2011. In 2015, people came out from a group at Oxford called the People of the British Isles study. It produced the British part of the map. If you look at our figure 1, it shows Britain and Ireland and all the samples on the British side of the map were collected and published as part of the British Isles study.

“What we did was study the DNA of about 200 individuals who we recruited to the Irish part of the Irish DNA Atlas. We all carry about 3 billion bases of DNA but we differ at about one in every thousand. So, if you sequence me and sequence you we will be 99.9% identical but we differ at 0.1% of points in our DNA and

that’s about 3.5 million points, so a tiny percentage, but still quite a large amount of data points.

“What we do is look at those differences between individuals and by doing that, you can create groups of genetic similarity, and this is where the 10 Irish groups have emerged. And it’s 10 so far, 10 robust groups. There’s a lot of similarities between individuals, with any group, to the extent that you’re more similar to a person in the same group as you than you are to an individual in another group. I stress, the differences are really subtle. It’s not as if you

can tell by looking at someone in another group that they’re in the north Munster group, you can’t. The differences are tiny but the analysis is getting sophisticated and the genetic data set so big that you can pick up these tiny differences at a genetic level.

“When you put people into these clusters and then you colour code people by the cluster, and then try and plot them on to the map of Ireland according to the average, where their great-grandparents were born, you can see that this creates a map where the groups correspond roughly with the provinces.”

What were the challenges in finding these people?

“Most people in Ireland don’t have that type of ancestry where all their great grandparents are born 50km from each other. The logic of choosing and having those criteria is that we wanted each individual in the study to represent, as much as possible, that particular part of Ireland. When you do that, you recreate a map of what Ireland would have looked like around 1850, say around the time of The Famine, or just after the time of The Famine. That’s the average

date of birth of the great-grandparents of the study.

“The challenges are, most people don’t have that kind of ancestry because people moved a lot over the last 50 or 100 years. If you look at me, my ancestry is Italian. I was born in Ireland, straight away I had foreign DNA coming in, married an Irish lady, we have two kids. My kids are going to have their DNA as half Irish, half Italian so everything is getting quite jumbled up. When you go back to the 1850s, there was much more structure in the Irish population.

“It was a challenge recruiting but the reward of that challenge, of being able to address it, was that you get these quite exquisite maps of subtle genetic structure across Ireland, a structure that mirrors the provinces and of course, the boundaries of provinces mirror all power basis in Ireland.”

What were some other key findings of the study?

“Other key findings were, we detected quite a significant signature of Norse ancestry in Ireland. We detected up to 20% of the Irish genome to be of Norse ancestry and it’s not just broad Norse ancestry, it’s ancestry specific to little towns along the west coast of Norway. These are known historically to have been Viking bases. What we’re saying here is, ancestry in Ireland, of Norse origin, correlates with the geographic location where the Vikings are known to have had a primary basis.

“The 20% is quite high. We think it’s probably an overestimate because it’s possible when the Vikings came to Ireland they actually brought people back to Norway and when you do that, you’re bringing Irish DNA back to Norway. When we look at Norwegian signatures today we have to assume it’s all Norwegian when, in fact, a percentage of it is Irish from the time of Viking raids. That can overestimate or conflate what we interpret as a Viking signal in Ireland. That was

certainly a key finding. We’ve shown for the first time there’s significant Viking DNA in Ireland. Previous attempts to do this show very low and inconclusive levels, even though we know there are Viking surnames. That’s why it was kind of a contradiction that we had Viking surnames. We know Dublin, for example, was a Viking base but we didn’t see this in the signature in the DNA. Now we are able to finally pick it up because the techniques are getting more sophisticated.

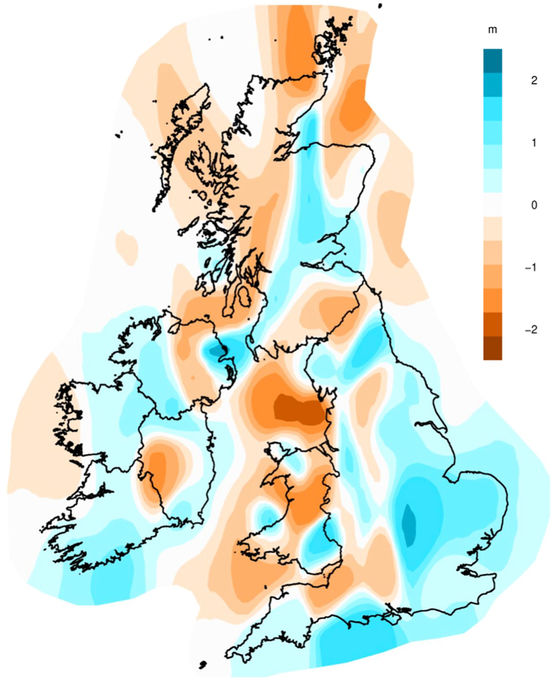

“The other thing we’re able to see, at a genetics level, is the signature of the plantations in the North and of course this is something we knew, you can tell from surnames and so on that certain people have planter ancestry but now, just at looking at DNA we can see quite clearly and it dates to the 1600’s around the time of the Ulster Plantation. There are other things, like if you look in Munster, we find that Munster splits into two groups, north and south and that’s kind of interesting. This might be a feature of the geography of Munster, of the mountain region splitting north and south Munster, but it could also reflect dynasties of say, the Dalcassians, who had a base in the north of Munster vs. the Eóganachta who were more centred around the south of Munster. That structure we see today in Munster might have a combination of geography and social structure as defined by kingdoms one thousand years ago.”

What are you learning from this?

“We’re learning there’s this subtle population structure across Ireland. It’s something we would have suspected but were never really able to show conclusively. It tells us Ireland has a lot of ‘Celtic Ancestry’ and by Celtic, I mean pre-Viking as there was a lot of controversy over exactly what that was. Certainly, we can say the influence of Saxons in particular on Ireland was minimal. Vikings made an impact, plantations made an impact in the North from what we can see genetically but otherwise, a very large percentage of our genome was present before the Vikings arrived. That’s interesting because if you look at the UK there’s less of that signature. It’s still there but it has been diluted by invasions such as the Saxons who came pre-Vikings.”

What does the future hold for this research? What could be the future benefits?

“First of all, we’re keen to recruit more people as it’s a live study. If people are interested in being involved they should email [email protected]. You need to have eight great-grandparents born within 50km of each other. With more people we can hopefully get more resolution in the structure and then the

genetic techniques are getting more sophisticated so that would give us more power to detect structure as well. We want to learn about Irish history.

“There’s also an application of this kind of concept to medical studies where there’s a lot of effort in trying to find genes for certain diseases, the genes that underlie hypertension, for example. By knowing the structure of the Irish population in the way we’ve illustrated it can create and empower better studies to find genetic factors underlying diseases.”